Tags

appearance, attitude, authoritative advice, certainty, cessation, collateral damage, condition, consultative, irremediable, joyful, observation, psychological, quality of life, risk, stoicism, termination

Dear Friends,

Summary

I learned last Wednesday that the 8th cycle of chemotherapy was typically the point at which the highest tolerable concentration of chemicals (er, medications) had been pumped into my body. Subsequent infusions were predicted to be accompanied by increasingly severe side effects. In fact, I’d experienced increasing discomfort resulting from the effects of the chemotherapy since the 8th cycle. I’d also suffered a rapid drop in weight, given the fact that solid foods were not only distasteful but were, in fact, disgusting. For that reason, alone, I could not stomach much beyond hi-protein packaged milkshakes and other liquids.

Monica had driven me to the Infusion Center last Wednesday, since she was “enjoying” her well-deserved week off for the Winter Holidays. Once there, we found ourselves in deep consultation with our specialists and nurses, and eventually concluded that we should terminate treatment on account of my condition, weight loss and distress.

I believe the decision to rank among the most difficult in my life. Following are some of its component parts.

Detail

Undeniably, I have a quirky way of dealing with decision-making. I believe my approach represents what other patients must confront (though I’ll readily admit they might not articulate it in the same way as I do). Following is the context of my thinking-process in reaching my decision. It is complex, as a decision concerning health-care should be.

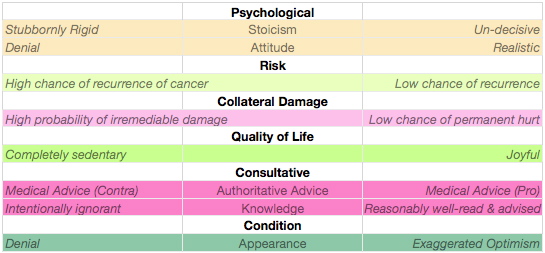

Complicating decision-making in the absence of certainty is the fact that the tightrope walker (in this case, me) is compelled to handle multiple different balance poles simultaneously (unlike professional tightrope walkers who balance one at a time).

Among the discrete spectral balance poles I considered as part of my decision-making are the following. They can be expressed (with no particular hierarchy in mind) in tabular form:

Psychological

This is an unavoidable attitude towards my cancer that is part of the way I approach life. I tend to be stoic about anything painful. Most of the time, I try to ignore pain until it goes away. Yet, to my mind, my attitude is reasonably realistic. I don’t carry my stoicism to extremes. While my “stoicism” balance pole is likely to be a bit off-center (since I generally understate and underestimate conditions that are painful or even harmful to me), it is not so badly skewed as to threaten the carefullness of my decision-making.

Risk

An obviously important concern is whether or not a cessation of treatment will expose me to greater risk of future recurrance of my cancer (or of another type as has been reported in the literature, at least some cases). Expert advisors are mixed in their opinion. One of the reasons I signed up for the Clinical Trial was my eagerness to participate in gathering data about divergent hypotheses. The problem, in the present instance, is that the data will not prove conclusive until many years into the future and therefore does not help me very much in making a decision today.

Given concern about my reactions after the 8th cycle, Monica and I were swayed by the fact that we had passed the 6th infusion (a point at which some doctors believe that the toxins have exerted their greatest effect on ridding my body of its existing cancerous cells). Though it appeared I could not endure the entire alternative protocol, I’d passed well beyond the mid-point of the extended protocol. This appeared to us as a kind of middle point between justified riskiness and danger from overexposure to the toxins.

Collateral Damage

Neuropathy has been often described as possibly irreversable, even after treatment ceases. After my 8th cycle of infusions, I experienced a decidedly sharp increase in neuropathic feelings in my fingers, toes, eyesight, taste and vocal cords. The effect on my physical extremities (particularly, feet) had even noticeably affected my balance. While none of the symptoms rose to the level of “life-endangering”, collectively, they were alarming; especially as I considered whether the neuropathy would persist long into the future. There appeared to exist no crystal ball from which I could glean an answer.

Quality of Life

Considering quality of life includes a present component as well as a future consideration, and is related to the above. How do I feel now? How might I feel if I continued infusing myself with caustic chemicals? My present condition has been debilitating in the sense that my ennui and lack of energy has turned me into a Rip Van Winkel-like couch potato. This is not a condition I enjoy. Nor is it one in which I can take pride. Akin to my problems maintaining a nutritional diet, it has been quite surprisingly difficult to overcome these maladies merely through will-power. This unexpected realization had an impact on my decision-making, to be sure.

Additionally, I counted the observations made by my family members. These suggested that my downturn was not imaginary. Their more objective—albeit to a degree, self-serving—observation identified a degraded version of their husband and father. Their observations (which I must trust) had a significant impact on my own judgement about my reaction to the toxicisity of my treatment and the ultimate conclusion that I should cease treatment at this point, and continue on this road in a watchful manner, along with my oncologist and general practitioner.

Consultative

I am intensely aware (and have become moreso as this process has evolved) of my ignorance of the complex details and intricacies involved in cancer research, evaluation and treatment. Countering such ignorance is what medical schools are for. I have not matriculated in one. That being a given, I consider myself to be reasonably well-read for a non-professional. I take my consultations with my oncologist as highly important and informative augmentations to my own research. Her advice is not to be overriden or ignored at a whim.

Nonetheless, I judge that there is a considerable ambivalance within the medical community, at large, about the current extended protocol of treatment. No one is able to tell me that ceasing treatment after ¾ of the maximum protocol of chemotherapeutic infusions is seriously risky. No one can assure me that holding out for 3 more (with the considerations listed above) is essential to success or empty of danger. No one can tell me that it is certain that 6 cycles, alone, will be sufficient to obliterate my cancer or insufficient to accomplish that aim.

Condition

It is part of my personality to conclude that my side effects are “not as bad” as they could be. But this personal inclination may minimize the fact that—for me—they ARE, in fact, bad. For a balanced view of this particular continuum, I must rely to a great extent on those who observe me, as from a distance. They generally feel that my condition is alarming enough that I should not ignore their desire that I (at least temporarily) cease treatment.

In consideration of all these individual spectra, I felt I had a reasonably balanced perspective. I felt I’d given an sufficiently fullsome consideration to the various influences on a decision that included no certainty about most of its aspects. One thing is obvious: this is not the end of the road, merely a stage stop along the way. The nurses predict that it will take 4-6 weeks for me to rid myself of the toxic effects of the treatment I’ve, thus far, received. I feel I’m slowly recovering strength… but its an amazingly slow process to me. I’ll need to work on the virtue of patience in my life!

As I left the Infusion Clinic—and despite all the welcome and expert advice I’d been given— I found that all the balance poles in my hands had jammed the doorway, impeding my exit. Can anyone help me? Anyone? No one? Hello?

Chet